Fast, affordable Internet access for all.

California digital equity advocates say that recent cuts to the state’s ambitious broadband deployment plan unfairly harm low-income and minority communities. And despite promises from state leaders that the cuts will be reversed, local equity advocates say the process used to determine which neighborhoods should be prioritized remains rotten to the core.

In 2021, California state leaders announced a $7 billion, multi-armed plan to bring affordable, next-generation fiber to every state resident. A key part of the plan involved building a $4 billion statewide middle-mile open access fiber network designed to drive down the costs of market entry, improve competition, and reduce broadband prices.

At the time, California officials said “the statewide network will incentivize providers to expand service to unserved and underserved areas.” Groups like the EFF lauded the “historic” investment, likening it to bold, early efforts to ensure rural electrification.

But last May, California officials quietly announced they’d be making some notable cuts to the state’s affordable broadband expansion plan. Blaming inflation and rising construction costs, the state’s renewed budget called for a 17 percent reduction in planned broadband investment, on average, across the state.

But marginalized California communities, like East Oakland and South Central Los Angeles, saw planned state fiber investment drop by 56 percent and 77 percent respectively. In East Oakland, 28 miles of planned fiber running along I-580, I-980 and State Route 185 has been reduced to a single strand of fiber that will no longer cut through the flatlands of East Oakland.

All told, state leaders cut broadband investment in these regions by around $28 million, and failed to transparently document their decision making process.

At the same time, the state boosted broadband investment in more affluent portions of the state, including projects in communities like Beverly Hills and Culver City. Activists were quick to accuse the state of redlining, and questioned a state decision-making process that once again disproportionately harmed communities long stuck on the wrong side of the digital divide.

When a Reversal Isn’t Really A Reversal

While outlets like the San Francisco Chronicle recently ran headlines saying that Governor Gavin Newsom had reversed the cuts after months of activist pressure, local community leaders tell ILSR that’s not actually the case.

“It’s not actually a reversal,” Director of the Digital Equity Initiative at the California Community Foundation Shayna Englin told ILSR.

“What the Governor committed to was his intention to ask the legislature for more money–probably A LOT more money–in next year's budget to fulfill his promises to communities like South LA and SELA with respect to the Middle Mile network,” she said. “His administration is moving full steam ahead on spending the existing $3.86 billion allocation for the middle mile Broadband Initiative without building out the much-needed routes in low-income communities of color–the same routes he announced nearly two years ago to great fanfare.”

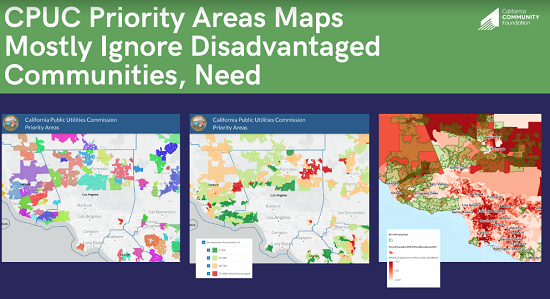

At the heart of the problem sits the California Public Utilities Commission’s (CPUC) broadband maps, which are being used by the California Department of Technology to determine which parts of the state should receive broadband funding priority.

Englin and other local broadband equity activists have long argued that much like federal broadband maps they’re based on, CPUC’s maps are inherently flawed; they dramatically overstate broadband coverage, downplay widespread competition issues caused by regional monopolization, and routinely fail to prioritize affordability and equity.

“These maps woefully understate the connectivity issues that I know to be true in my city,” Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao wrote in a letter to the California Department of Technology last month.

Activist groups like Digital Equity LA have had some success in pressuring the CPUC to improve its mapping standards to prioritize equity and affordability.

One bill winding its way through the California legislature (AB 286) would include crowdsourced mapping data and allow individuals to challenge inaccurate coverage claims. Another (AB 41) aims to reform California video franchise laws with an eye on ensuring even and equitable deployment of next-generation broadband. (ILSR, along with a coalition of digital equity advocates, were initially in support of AB 41 until it was littered with industry friendly amendments that effectively gutted the bill. Last week, ILSR sent a letter to Gov. Newsom’s office which requested he veto the bill.)

Still, the underlying data and methodology currently being used by California to determine broadband funding has long been heavily shaped by the interests of the state’s biggest broadband monopolies–with a sharp focus on their expedited profitability.

“By refusing to address the demonstrably wrong maps that show wealthy neighborhoods disconnected and low-income communities as fully connected - maps that are widely acknowledged to be woefully and systematically wrong - the Governor has opted to extend this problem beyond the Middle Mile and to the rest of the Broadband for All programs,” Englin said.

Activists say that fixing the problem will require not just restoring broadband funding to marginalized California neighborhoods, but a complete rethinking of the state policy decision-making process with an eye on public transparency.

“Bureaucrats sitting in a back room in Sacramento in between public meetings, making gut decisions on how to spend $4 billion in public money is not how this is supposed to work,” Englin said.

Redlining Continues To Be An Ugly Nationwide Problem

Organizations like the National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA) have spent much of the last decade documenting how regional telecom monopolies routinely refuse to install, upgrade or even repair broadband connections in low income, marginalized communities despite more than thirty years of heavy taxpayer subsidization.

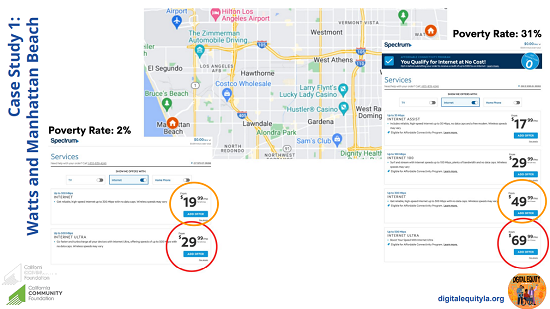

Meanwhile, advocacy groups like Digital Equity LA have published studies showing how low-income Los Angeles residents pay significantly more money for what’s often slower broadband. Extensive reporting from media outlets like The Markup have also illustrated the same problem nationwide.

At the heart of the digital divide sits giant regional telecom monopolies whose political influence ensures that federal broadband policy prioritizes profitability over affordability or equity. These same telecom giants are routinely gifted with massive tax breaks or regulatory favors in exchange for network upgrades perpetually stuck just around the next corner.

Telecom giants routinely deny that they factor income or race into broadband deployment decisions, but the data collected by groups like the NDIA in cities like Detroit or Cleveland paints a clear picture when it comes to demographic discrimination.

Despite decades of evidence that redlining, or what the FCC calls “digital discrimination,” is a large problem in broadband deployment, only in the last few years have federal policymakers even started to more seriously consider affordability and equity in broadband mapping and policy considerations.

Agencies like the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) only just began including affordability and equity in both policy and mapping, while the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) forced the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to create a digital discrimination task force to study and address redlining in broadband deployment.

“Addressing digital discrimination and redlining is a critical piece to living up to our standard of equal access to the infrastructure needed for 21st century success—no matter who you are or where you live,” FCC boss Jessica Rosenworcel said at the time. “Your zip code should not determine access to broadband.”

Unfortunately, little in the way of serious reform has come from the FCC’s announcement so far, though by law the FCC’s proceeding is supposed to be completed by November. Whether the proposal results in meaningful, widespread reform is far from certain.

Federal inaction on this subject is directly reflected in California, where activists say there’s massive work to be done if the state’s ambitious broadband plan is to genuinely deliver on its original promise of equitable, affordable access for all.

“This process is so broken it can’t just be papered over,” Englin said. “Throwing more money down the rabbit hole won’t fix what’s rotten at the bottom: bad data, no transparency, no accountability, and no community engagement.”

Header image of California State Capitol building courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Inline image of East Oakland courtesy of Flickr user Clotee Allochuku-Albritton, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)